Spy Arts

The Lying Dead

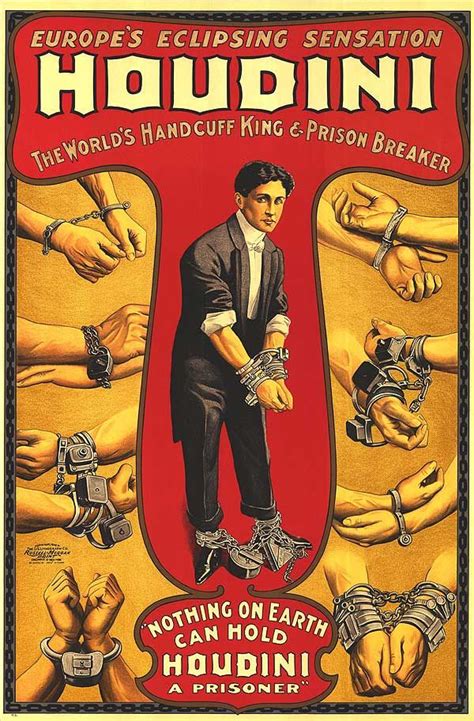

Harry Houdini, Arthur Conan Doyle

& the Spiritualists in a Grieving World

Spiritualism has many followers, and at one time I was almost a believer. –Houdini

When you get there, he is waiting for you several yards inside the gate, meeting his visitor’s eye. His head has been smashed, stolen and replaced over the near-century since his body was interred, yet he holds his audience with an imperious gaze. Even in life, his head had seemed to Edmund Wilson like an enlarged bust of a Roman general, “wide-browed and aquiline-nosed.” Beneath him, a veiled woman leans on a granite bench in sculpted grief.

Small stones often dot the grave, left to honor the anniversary of his passing, on Halloween. The offerings are periodically gathered up; most are plain, some stickered with his image.

Thirteen years before his death, he buried his beloved mother here, lying beside her grave some nights unburdening himself in the depths of his mourning. “Here in Eternal Peace, Slumbers our Darling Mother,” it reads on her stone marker, “As Pure and as Sweet as the Day She was Born.”

Houdini was 52 when he joined his parents, two brothers and his grandmother in this Queens cemetery in 1926, closed inside a bronze casket built originally for a stunt he’d called “Buried Alive.”

* * *

The train was on a six-month tour across the country, pulling the equipment for Harry Houdini’s one-man mystifying circus. Traveling with him was a bronze casket built for an escape stunt called ‘Buried Alive!’ along with his ‘Water Torture Cell,’ a watery glass box in which he hung by his ankles; cabinets built for vanishing glamorous assistants, a set of fake alarm clocks to hurl across the stage for the ‘Flight of Time’; and spools of scarves pulled hand over hand to create his ‘Whirlwind of Colors.’ Also aboard were his wife, Bess, a nurse, and his loyally secretive staff. It would be his last campaign.

Taking a winding route from Providence through upper New York State, the tour reached Montreal on October 19th 1926, its star limping from an ankle twisted in the stocks of his Water Torture Cell while entertaining in Albany. According to his hosts, the magician and his wife seemed to be sharing a nurse in Montreal, Bess for a bout of ptomaine poisoning and Houdini for his wounded ankle as well as a mysterious condition that left him weary and pale.

The latest tour incorporated Houdini’s favorite illusions and escapes with a demonstration of his recent cause, debunking what he called ‘spirit frauds.’ For each town he sent his investigators ahead to dig into the practices of local mediums, announcing their findings from the stage to delight the crowd as well as outrage true believers. With volunteers from the audience, he performed on-stage seances in order to deconstruct their methods. Houdini accumulated lawsuits with his revelations, which gained him both publicity and enemies.

He had received many threats on his life. “I am marked for death,” Houdini brooded. “They are predicting my death in spirit circles all over the country.” The most famous threat had been the ‘astral curse’ put on him by the Boston medium ‘Margery,’ who announced he would be dead by December 21st 1925, a date whose passing led Billboard to mock, “Margery’s crystal seems to be a bit misty.”

On the day he was to open at Montreal’s Princess Theater, October 19th 1926, Houdini was also invited to speak at McGill University to students in the Union Hall. He seemed a bit uneasy standing on his tender ankle through the afternoon talk, but charmed the group with his lecture on ‘spiritualism fakes.’ At the close, he gratefully sat and took questions, one medical student asking how he might explain the effects achieved by the fakirs in India, who were said to pop out and replace their own eyes and run needles through their cheeks. “Those are just tricks,” Houdini scoffed, asking for a needle to demonstrate. The psychology department head declined to assist him, “I do not approve of what you are going to do,” but someone produced a needle and Harry proceeded to poke it through his cheek, then asked one of the McGill students to pull it out. There was no blood, a reporter noted.

Another young man in the room, Sam Smilovitz, sketched Houdini as he talked, but would remember he looked pale and a bit tired. When he shared the drawing with his fraternity brothers, they brought it to that night’s performance and showed it to Houdini, who admired the likeness and asked that the artist come to his dressing room the next day to complete a posed portrait for his own collection. He agreed, and ended up being deposed for what he saw.

Smilovitz and a fellow student appeared before noon at Houdini’s dressing room, and began talking and setting up to draw his portrait while Houdini relaxed on a divan sorting his mail, apologizing for laying back for some needed rest. A third young man, a first-year Dental student named Whitehead, joined the others in the small room.

Whitehead had many questions about magic and religion and strength. He asked Houdini, according to the others, if it was true that “punches in the stomach did not hurt him.” However poorly he might have been feeling, Houdini nodded, too proud to turn down a challenge, while attempting to steer the subject to the strength of his chest and arms, which he offered for examination. Before he could stand and ready himself, Whitehead suddenly began to pound on his abdomen, some of the hard punches “below the belt” according to the two astonished witnesses. “That will do,” Houdini finally said, making a pleading gesture to end the punishment. But he gamely still allowed his portrait to be finished after the incident, telling Sam Smilovitz, “You made me look a little tired in this picture. The truth is, I don’t feel so well.”

* * *

His appendix, likely already infected, had not been helped by the pounding he received. The tour reached Detroit in the early hours of October 25th 1926, its star wracked with abdominal pain and hot with fever. A doctor Houdini had wired from the train met them at Michigan Central Station and judged he suffered from appendicitis. Having performed through illness and injury in Canada, his first instinct was still to retire to his suite at the Statler Hotel and rest for his opening night. His condition worsened at the hotel, but he took the stage that night, collapsed during a break, and staggered on to complete his two-and-a-half hour program before falling into the arms of an assistant offstage. It would be his final performance.

He entered Detroit’s Grace Hospital, where surgeons analyzed that the poison from his infection had been circulating in his system for some days, perhaps helped along by the strong abdominal punches he received in Montreal. But the poison had been traveling about his body before the beating, as Sam Smilovitz’s sallow likeness of him made clear.

Doctors quickly operated that afternoon, then issued a statement: “The appendix had ruptured far over on the left side of the abdomen and a streptococic peritonitis has developed as a result of the rupture. Grave doubts are entertained for his recovery.” The hospital’s daily reports seemed meant to prepare the public for the worst, their tone changed briefly from bleak to sober when his fever was lowered thanks to an experimental serum whose name they would not disclose, for fear its maker might be blamed for Houdini’s death. When a second operation was performed on October 29th, for a blocked bowel, the feeling of a death watch returned: “His condition is very grave, but hope for his recovery has not been entirely abandoned.” His brother Theo, a fellow magician who performed as Hardeen, reported Harry ‘s words, “I can’t fight anymore.”

Houdini was pronounced dead on the afternoon of October 31st, Halloween, five days after entering Grace Hospital. Credit was quickly claimed by his enemies. “[T]he spiritualists –that is, the dark-room-séance-and-table-tapping spiritualists—are all glad Houdini is dead,” a psychic friend of the magician’s named Marian Spore reported. “They tell me the spirits did it.” The argument began over what exactly had killed him and how he had achieved his astonishing stage effects. “No human being could do the things that Houdini did without assistance from the invisible world,” claimed Rev. H.P. Strack, general secretary of the National Spiritualist Association. The story that he had died from a punch to his gut grew loud enough that the McGill professor who had hosted him issued a statement: “There is no truth in the Detroit report that Houdini was injured in a sparring bout with a McGill student.” Another story went around that young Whitehead had been an assassin whose fist was guided by spirits.

His touring show had been hauling the bronze casket for his ‘Buried Alive’ stunt, but when the tour’s equipment traveled on without him, the casket was left in storage. It would now be put to earnest use: He was laid inside it for the train ride home with his wife Bess. “No one knows what I have lost,” Bess would say after accompanying her husband’s body in a private Pullman from Detroit to Grand Central.

In New York, his service was attended by some 2000 people at the Elks Club lodge no. 1 on West 43rd Street, near Times Square. Bess nearly fainted watching them screw the casket lid closed before it was covered in flowers, a magician’s wand snapped in half over the coffin to symbolize the end of Houdini’s powers. Whatever Harry had thought might happen following his death, he knew exactly the people he wanted to see him on his way out, the celebrated figures he invited to be his “honorary pallbearers,” from Adolph Ochs to Bernard Gimbel and Martin Beck, who’d discovered him, honored guests not called upon to carry him.

Hundreds lined the sidewalks, some removing their hats, as the cortege of 50 cars traveled slowly out to Machpelah Cemetery, where he was borne to the grave site by a troupe of his assistants. As the casket disappeared into the grave, flowers were tossed after it. As his funeral plan specified, he carried something familiar along with him into the grave, buried with his head lying on a bag of secrets –a black pillow filled with letters from his mother, comforting him on his journey.

He chose Bess Houdini to place the pillow there, and to read his mother’s letters first if she wished, although Cecilia Weiss’s devotion to her son can hardly have been a surprise to Bess. If the letters could not be found in time for his burial, he instructed they be burned. Bess also held a secret code for verifying possible messages from her husband. “Many years ago,” she explained, “Houdini and I formulated a code which we agreed the first of us to die would use to communicate with the other. We did not believe in spirits but had open minds.”

Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and spiritualist champion of the age, announced upon hearing the news of the death of his old friend: “His death is a great shock and a great mystery to me. He told me much in confidence, but never secrets regarding his tricks…We agreed upon everything excepting Spiritualism.” Sir Arthur also revealed that a message predicting the death had been received by his wife from the magician’s late mother at a séance: “We withheld the message from Houdini, hoping that it might prove she was mistaken.” It was not the first time Lady Doyle had spoken for Houdini’s late mother.

*. *. *

In the spring of 1916, the third year of the Great War in Europe, Arthur Conan Doyle was asked to visit three Allied fronts –the British, French, and Italian– and to record his impressions in a pamphlet for the War Office.

We cross a meadow and enter a trench. Here and there it comes to the surface again where there is dead ground. At one such point an old church stands, with an unexploded shell sticking out of the wall. A century hence folk will journey to see that shell.

Conan Doyle had once covered the Boer War and written a patriotic history of the conflict. Now in his fifties, and turned down as too old for active service, he had watched his elder son Kingsley, a young medical student, go off to the war. The big guns near the French front could be heard like distant thunder some 100 miles from the Doyle estate in East Sussex. The Doyle family began taking seances together as they waited to hear about the fate of British troops. That May of 1916, when Arthur toured the Western front, young Kingsley Doyle was brought up the line to see him, near Mailly, with “his usual jolly grin upon his weather-stained features.”

Weeks later Kingsley would be among the 100,000 soldiers attacking the German line at the Somme, in the mass offensive of the British Expeditionary Force. To prepare the way for the battle, a week of heavy Allied bombardment preceded the attack, in hopes the bombing campaign would clear the way for the infantry marching in to take German territory. But the commanders did not figure on just how deep the German shelters would be, many dug 30 feet below ground for withstanding the shell blasts. Although vastly outnumbered on the ground, the German soldiers were able to bring their machine guns up out of hiding to meet the unsuspecting lines of infantry marching towards them on the morning of July 1st 1916, which became the bloodiest day in military history. On the British side nearly sixty thousand casualties fell, 19,024 of them killed.

Kingsley Conan Doyle, a handsome, square-jawed young man with a neatly parted mustache, was shot in the neck that day, but could count himself comparatively lucky. Unlike many of the wounded who died pinned down in No-Man’s-Land or were hung up on the enemy’s barbed wire, he was retrieved from the field and able to be treated while scores of men died waiting to see Army surgeons.

Kingsley recuperated and survived a return to service, coming home a decorated veteran in 1917. It was after he rejoined civilian life, hoping to take up his medical studies again at St. Mary’s college, that he contracted the virus that would kill him. An Influenza epidemic was sweeping the world in 1918, and Kingsley died October 22nd at St. Thomas’s hospital in London, weeks before the armistice. He was one of 14 London influenza deaths listed in the day’s Times. Arthur saw his son’s body a final time at the morgue, where he looked “his brave steadfast self.” Within days of Kingsley’s death, Arthur spoke to an audience of Spiritualists at Nottingham on the subject of “life beyond the grave.” His boy was not truly gone from him, he assured his listeners. One night at a séance, Kingsley would visit his grieving father, dutifully apologizing for ever doubting Spiritualism, like a good son.

The influenza also claimed Conan Doyle’s younger brother Innes. After the passing of their friend and medium, Lily Loder-Symonds, his second wife, Lady Jean Doyle, who’d lost a brother in the early fighting at Mons, began developing skills as a slate reader, taking dictation from spirits with automatic writing.

One evening in the summer of 1922 in the Doyles’s seaside hotel suite in Atlantic City, she would feverishly scratch out twelve pages from Houdini’s late mother Cecilia as Harry silently watched, Sir Arthur turning each page as it was completed. The two men’s responses to what had happened in that room would crack their friendship and its polite truce over the supernatural. “You are to me a perpetual mystery,” Arthur had once written him. “No doubt you are to everyone.”

Conan Doyle hoped to have the last word on the firestorm Houdini created, to claim him for the other side in a debate that had begun in the aftermath of the Great War; the accumulated horrors of four years of death and sacrifice and a worldwide pandemic had left behind millions of mourners, and produced scores of mediums promising them contact with lost loved ones by the early 1920s. As mourners escaped into Spiritualism, Houdini’s debunking of ‘spirit fakes’ had stoked a national debate, and made an antagonist of his friend.

In their public battle during the 1920s, Houdini and Conan Doyle personified reason and spiritualism much like the showdown of science versus religion then waged by Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan at the Scopes “Monkey Trial.” The backlash against science and modernity would find its echo a century later in a public exhausted by a second deadly pandemic.

* * *

Upstairs in a midtown magic shop, after store hours are over on Tuesday and Thursday nights, there is another ritual for summoning Houdini and feeling his presence. There is an old iron tub in the store in which Houdini was said to bathe a hundred years ago and practice holding his breath underwater; above the scuffed white tub sits his imperial head, scrutinizing the room from a glass box.

It is the twin of the bust that tops his granite exedra in Queens, the large head he had commissioned in London before his death. After being stolen from the gravesite, the bust turned up years later in someone’s storage facility and was lovingly copied for its celebrated return to the cemetery. The upkeep of Houdini’s grave is the responsibility of the Society of American Magicians (an organization he founded) and Harry’s recovered head holds court not six feet from the table where Noah Levine regularly performs close magic in the dark for a circle of guests at Tannen’s magic shop.

Houdini watches every performance closely, and as the lights go down and playing cards are laid on the table, his spirit fills the room.

Life in the Tombs

The Sequel to Ashes of My Youth: A Tale of New York & The Wall Street Bombing Life in the Tombs continues the story of New York crime reporter Johnny Moran in 1925 Chapter One: To say I was untethered in those days would be putting it limply; in the open air of the Sixth…

Coming This Spring

Ashes of My Youth: A Tale of New York & The Wall Street Bombing By the author of The Lost Detective: Becoming Dashiell Hammett, nominated for the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Award and the Anthony Award. Now in the Kindle Store: https://www.amazon.com/ASHES-MY-YOUTH-Street-Bombing-ebook/dp/B0949MDSDF/ref=sr_1_1?dchild=1&keywords=Ashes+of+my+youth&qid=1620397501&s=digital-text&sr=1-1 Escaping from the house of his Hoboken ward boss father, young Johnny Moran enters…

ASHES OF MY YOUTH: A Tale of New York & The Wall Street Bombing

Coming This Spring from Spy-Arts Excerpt: Manhattan, 1935 We had switched from beer to a pair of hot rums dubbing around in a reporters’ bar across from the women’s prison downtown. Outside it was storming in late October style, the first chilly rain that gnaws like winter, and from our polished stools we watched the…

Confessions of the Outlaw

Coffeyville, Kansas 1892 Trains brought people from nearby towns, who sliced keepsakes from his dead brothers’ clothes where they lay; clipped hair from the manes and tails of their fallen horses and cut the strings off their saddles. In the street, he was nearly picked over for souvenirs himself before he was carried upstairs, where…

George Plimpton Broke My Arm

Introduction: What’s a Havlicek? I was not yet much of a sports fan, except for watching the jumps and spills of Evel Knievel, when my family moved from Long Island to a cranberry bog town outside Boston in 1970. Almost everyone there was crazy for Bruins hockey, especially for the chestnut-haired idol of that bareheaded…

Follow My Blog

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.