Coming This Spring from Spy-Arts

Excerpt:

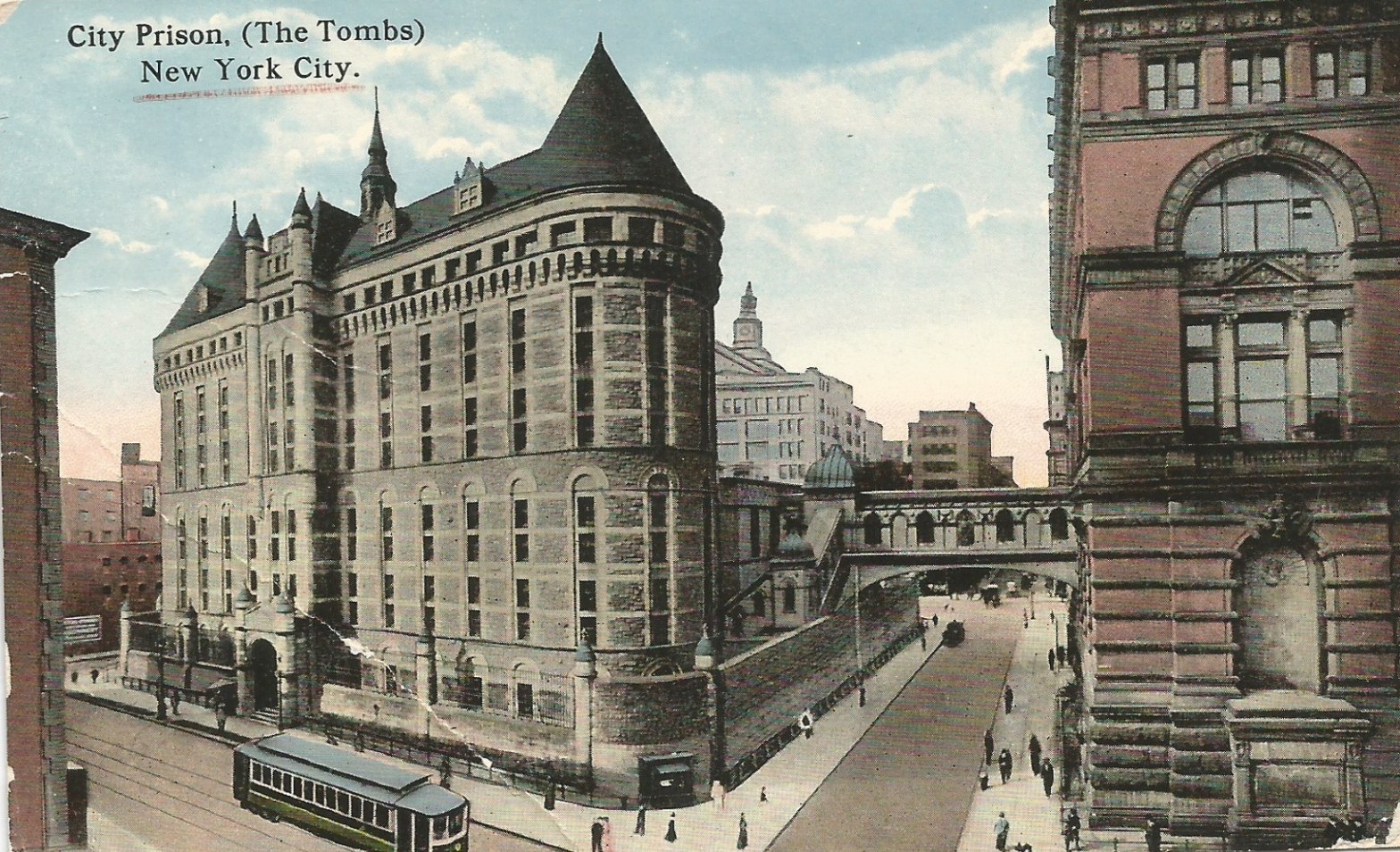

Manhattan, 1935

We had switched from beer to a pair of hot rums dubbing around in a reporters’ bar across from the women’s prison downtown. Outside it was storming in late October style, the first chilly rain that gnaws like winter, and from our polished stools we watched the people tilt their umbrellas at one another like blind knights as they passed.

The rum warmed our hands and insides as we watched for the last haul of ladies to be brought in before the midnight deadline turned our stories into pumpkins. My friend from the Herald, Red Hughes, and I were waiting with our fellow news types for the killer Eileen Meola to take her police-escorted sashay into the prison. We were hoping for a long enough glimpse to write in our morning editions whether her young face was pinched with guilt, flashed defiance, or showed only a forced sleepy calm of the just. About eleven-fifteen, Red nudged my elbow and gave two knowing clucks as I was wringing the last heat from my cradled rum, “Here comes something.” The police wagon had rolled up with a full load of sisters.

The consummate legman, Red scurried across the street and claimed a perfect assassin’s spot for the ragged procession in the time I took to drain my mug and fumble for my hat. It was hard to make out the self-widowed Mrs. Meola, between the rain and the dark circle of cops that moved at cortege pace. At the back, one officer held a single black umbrella high above the group in a civilized gesture that offered little shelter from the spattering. When they passed us, though, the cops were shepherding not the killer of the week but just a brightly-dressed chorus from a Village brothel, the rain spotting their jade kimonos and pink house robes. The scent of their mingled perfumes was like a vivid homecoming, transporting me along a path of magnolia and rosewater to the cathouses of my youth.

By now, I was pretty hardened to the people I saw dragged in nightly on my job, but a few still drew my sympathy, even curiosity. In the old days, the raid of such a house would be unusual, but my eye was caught by something else. At the center of this bunch instead of a young widow was a plump, proud woman I vaguely recognized with hand-drawn eyebrows and crimped red hair. I doubted myself at first the way people cringe at any fleshy proof that time has passed. Then I saw she was a tumbledown version of one of the girls who had sometimes met me at the door of Mrs. Kennedy’s place in Chelsea in the old times, waving a cigarette in her scarlet pajamas. That West 25th street rowhouse had leered yellow light like a jack o’ lantern down its block while teasy piano lines tumbled from it and filled the young visitor with expectations of worldly adventure like he was approaching the Cunard pier.

Names are part of my business. True, we had been younger and working nocturnal jobs not known for their virtue, but considering how many faces a person met in her line of work, I doubted this older Angeline could make me out all these years later under my hat and Mac. She was used to shamefaced clients looking away when they saw her out of doors, but here she had spotted me directly staring, and turned to size up the gawker in the slanting rain.

“Do I know you, Mister?” she smiled. “Maybe I used to know you, eh Johnny?”

The sergeant who’d helped her down from the wagon chuckled and swabbed drops from his broad red face with a pocket rag. “Should I leave you two alone, Moran?”

“Lucky guess,” I lied. “I bet she’s met plenty of Johnnies.” Angeline winked. “All these reporters for me?”

“Might as well be.”

The others laughed and there was a push from the back of the group. “Let’s move, ladies,” said the sergeant, still grinning. Angeline and the other sisters shuffled familiarly up the wet stone steps into the jail.

The press boys retreated back to the bar across the avenue to wait for our deadly widow, but she didn’t show that night. Mrs. Meola was still confessing somewhere else to a couple of poker-faced detectives, unspooling for their weary stenographer an epic line about her departed husband, left gutted and mute with a fruit knife. There was no press viewing of either Meola that night –the chatterbox or the corpse.

Long after deadline, we broke up the party and I said goodnight to Red. Then I wandered, a bit rum-lightened, in that hour where last call grudgingly gives way to the wholesome clop of the milk wagon, thinking about the faraway times dredged up by the sight of an ageing hooker in the rain. The rain by now had quit, but there was still a hanging chill in the air as I considered all the nights I’d spent in Mrs. Kennedy’s maroon rooms during that dangerous fall of 1920, soothing my grief over someone whose death I felt I’d aided, Belinda Harris.

As a young man coming to Mrs. Kennedy’s from the day’s arson trial or bank holdup, the trick had been to keep a reasonable likeness of Belinda in my mind’s eye when met in the gaslit hallway by Clara or Angeline or the one called Queen Mary because she recited Shakespeare in the dark. Then past the upright played by the old man in the cowboy hat–-days he built matinee crowds to a swoon at the 23rd street picture house–and then upstairs, where afterwards you breathed the lilac and cigarette scent of a figure lying back grandly on her elbows with one of your glowing smokes.

I spent a strange season at this game, and learned the piano player’s complete jolly repertoire, a boy attended by Mrs. Kennedy’s troupe until my troubles began to wear on the girls. At the time I had entered that leering rowhouse the first yellow leaves were curled along the city walks, and when I quit my game and came squinting into the light I found what Queen Mary would call a bare ruined choir. I have often been more lucky than smart, knowing you could stumble into the story that makes a career or the person who haunts the rest of your days while just eavesdropping in the butcher’s line or stooping to pick up your hat. Both had found me during my first months in newspapers.

Some of my friends, an eye on the hobo jungles and breadlines of the present, have written memoirs casting the early ’twenties in a golden light, as if Manhattan was then peopled entirely by movie actresses, baseball heroes, and gentleman bootleggers all waiting to slide your cocktail down the bar and invite you to that night’s rooftop rhumba. In these books, the author’s roving spot seems to flash on these characters anywhere it is pointed, as if reporters then were just wise-cracking caretakers in a celebrity zoo.

But in my experience, I often got little more than echoes of the famous people I had missed while covering shabbier storylines; waiters pointing out Arnold Rothstein’s favorite chair to me or losing at cards to the man who taught Louise Brooks to play whist; hearing fellow reporters brag how they shoved Dempsey back in the ring after he fell on their typewriters against Firpo; seeing Babe Ruth’s clay pipe hung above me while I ate my steak at Keens, or hearing Mary’s account of escorting the Babe home with another hired girl, stumbling together from the Taxi to his rooms at the Ansonia for a night that fizzled into watching the Bambino snore.

Often when I start to tell my own story of how I came to write my crime column, Life in the Tombs, it means I’ve stayed too long at the party. But hear me out: This is not my account of a golden time before the breadlines. It is mainly for the pleasure of summoning the living Belinda Harris that I’ve written about that autumn of the bomb and the flossy nights that came before.

***